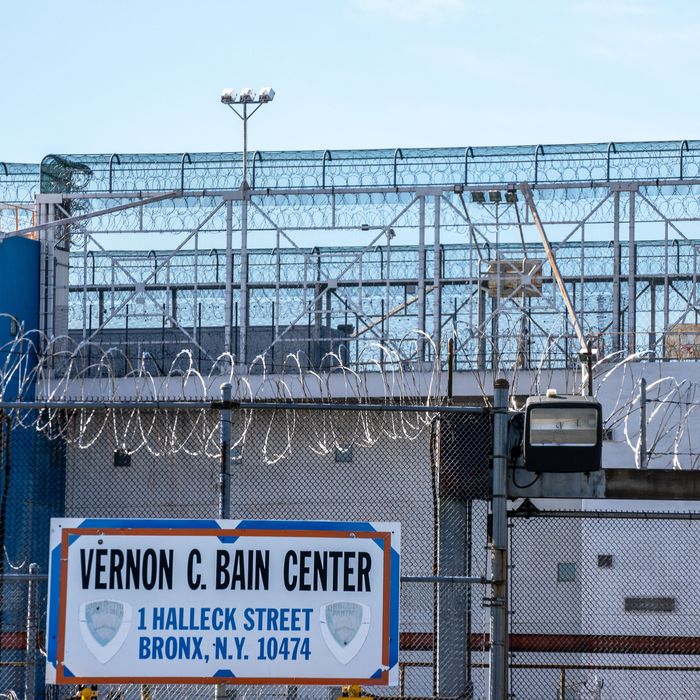

The jail’s associate warden rolled up his sleeve, readying himself for the vaccine. There was an unusually large audience for someone receiving a quick shot: a group of incarcerated men, security staff, and the chief medical officer of New York City’s jail system. It was 2009, in the midst of the first global flu pandemic in 40 years. The crowd at Vernon C. Bain Correctional Center — the royal-blue-and-white barge moored just off Hunts Point better known as “the boat” — rocked slightly during the uneventful show. After all, it was only a shot.

Months earlier, the governor had called a state of emergency as the swine flu spread throughout New York and the rest of the country. With a vaccine finally available to the city’s jail system after months of political squabbling and the introduction of piecemeal safety measures came a crucial test: Would incarcerated people actually get vaccinated? At that time, vaccination theater, like the shot conducted on the boat, became part of a concerted effort to sell incarcerated people on the vaccine. Now, with COVID vaccine rollout for people 65-plus underway in New York prisons as of February 5, the same question lingers: Will enough prisoners actually take the vaccine?

“I’m actually afraid to take it, mainly because there’s too little information available,” said Darr Williams, who is incarcerated at Shawangunk Correctional Facility in Wallkill, New York. He also says he’s seeing correctional officers decline the shot: “Officers still continue to bring the virus into the facility, refuse testing, and are now refusing vaccination.”

The trust gap at Shawangunk runs deep: Prisoners report drinking “prison potions” made with honey, ramen seasoning, and garlic to treat colds, or putting toothpaste on cuts when medical treatment is untrustworthy or simply unavailable. But Williams is a great example of someone who could distribute information about the vaccine: He is the coordinator for the Prisoners for AIDS Counseling and Education program, and has taught classes on HIV and hepatitis C in the prison for a decade. And he’s not alone: Currently, he oversees 14 facilitators who offer education, counseling, and support to incarcerated peers. But no one is asking.

The swine-flu outbreak in 2009, as with the current pandemic, was similarly marked by spread inside correctional facilities, and mistrust of the vaccine. (Williams, for example, declined to take the swine-flu shot while incarcerated for the same reasons he won’t take the COVID vaccine.) But COVID is markedly more deadly, particularly for Black Americans, who are dying at 1.5 times the rate of white people. Prison populations like New York’s, which is nearly half Black, are particularly at risk: There have been more than 5,500 confirmed cases of COVID-19 among the roughly 38,000 people in state prisons, and more than 4,400 cases among corrections staff. Thirty-one prisoners and seven staff members have died. As of today, less than 10 percent of prisoners have been vaccinated, and prisoners report virtually no outreach efforts.

Jonas Caballero, who served 25 months in Brooklyn’s House of Detention and Greene Correctional Center upstate before his release in December 2019, says he struggled to receive medical attention and care throughout his sentence. Appointments with specialists were repeatedly canceled; a doctor fell asleep during a consult; all four of his limbs were cuffed to a hospital bed following a cardiac event. Caballero says his “trust in the correctional medical health system was pretty much obliterated.”

“When there’s something as crazy-scary as [the] coronavirus that comes into the picture, for people that have had substandard experiences with health services like I did, it begs the question, are you really going to have people volunteering for [the vaccine]?” said Caballero, who now works as a paralegal for the Abolitionist Law Center and plans to attend law school. “Especially now, when everybody’s on lockdown for 23-plus hours a day, suddenly they’re going to say, ‘Hey, come on out of your cell and let us stick a needle in your arm?’ You can just imagine there would be some apprehension.”

In addition to that lack of trust, there is also the outright fear of experimentation. “We just don’t want to be the lab rats,” said D, a 45-year-old incarcerated in North Carolina who has worked as a self-taught jailhouse lawyer for 19 years and is an advocate and spokesperson with Jailhouse Lawyers Speak. “Today, when you look at disparities in the health care systems, you’re looking at Black people at the bottom. You’re looking at doctors who really don’t care anything for us.”

While there is no way to mend generations of harm overnight, small trust-building exercises have proved successful in the past. Williams suggested that prison officials distribute information about the vaccine and any potential side effects, while Caballero said that having an outside organization do outreach to prisoners without the involvement of correctional health staff would help foster trust. And then there’s the question of correctional officers themselves.

“I think it would help impact some of the thinking if we saw staff getting it first,” D said, noting that the Federal Bureau of Prisons has already opted to vaccinate staff first. “We feel like they’re not going to kill their own staff off like that — even just having the staff just come back and say ‘Hey, I had the shot and I’m okay.’”

That approach proved successful on the boat back in 2009. “Getting the vaccine at the beginning of the day in front of a huge number of people in the jail had this tremendous impact,” said Dr. Homer Venters, the former chief medical commissioner for the NYC jail system and author of Life and Death in Rikers Island.

After watching the swine-flu vaccination go off without a hitch, security staff and people detained in city jails alike lined up to receive the shot. Venters says he had to send back to Rikers twice for more vaccines to meet the demand.“We can’t undo all of the fractured relationships between correctional patients and correctional health services in one fell swoop, but I think this is an opportunity that requires that we start reaching out to our patients, understanding their concerns, and thinking how we can meet them with education and engagement,” Venters says. “These really are life-saving interventions.”