Chris Cornelius is an architect, a citizen of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin, and the newly named chair of the department of architecture at the University of New Mexico. Both his architecture practice and his teaching are informed by an Indigenous perspective that prioritizes environmental responsibility, and his designs often translate elements from folktales into built form. Take the studio:indigenous founder’s unbuilt proposal for the Oneida Visitor Center, which features an observation tower offering visitors the perspective of the Sky Woman from the tribe’s creation story. This year, Cornelius taught a design studio at the Yale School of Architecture and is also one of the inaugural fellows at the Forge Project, a Native-led initiative headquartered in the Hudson Valley with a modular guest house designed by Ai Weiwei. Following Cornelius’s cross-country move to Albuquerque (where his new campus sits on the traditional land of the Pueblo of Sandia), we talked over Zoom about land transfers, a tree funeral, and tricksters.

You have a unique practice that centers indigeneity as both an architect and as an educator. What was your path like to get here?

At first, I didn’t think about how I was going to incorporate my culture. I just thought I’d learn to be an architect and then work for my tribe. But in grad school, I started to build this critique. I thought there had to be a better way than the school shaped like a turtle on my reservation, which references Turtle Island, an Indigenous name for North America. You know, what Robert Venturi calls the “decorated shed,” like that duck-shaped egg stand? That’s not what I was trying to do! I started to think about how I could translate stories in a new form and in a more experiential way. Around the same time, I figured out I wanted to teach. I started to ask, “How can we make more empathetic designers?” At the moment, I’m doing Indigenous design work mostly for non-Indigenous clients, a lot of them universities. These institutions see the value of indigeneity, but they don’t know how to integrate it into their physical space.

I feel like there’s a lot more awareness of the value of Indigenous content. But we see good intentions sometimes result in institutions “doing the right thing” in the most tokenistic or superficial way.

Well, that’s the thing. Land acknowledgements are big right now. And institutions should be acknowledging the land that they’re on and doing it at every public event. But that’s one step. And it shouldn’t end there. What are the next steps? For me, it’s thinking about how we can create models of giving land back to Indigenous people. And I don’t think that that always means large swaths of land. What if in Detroit, some of these vacant lots were deeded over to Indigenous people? It can happen in a spectrum of ways.

An important part of your teaching practice is the translation of Indigenous knowledge to the next generation of designers. Climate change has been a wake-up call that the current paradigm and the values of settler colonialism — like the domination and exploitation of nature — are not sustainable. How should we be approaching this shift from a design context?

Climate change is a crisis of estrangement. So how do we correct that estrangement? I don’t think that the answer is solely in checklists and certifications and just creating a bunch of building standards. We’re going to extinguish ourselves if we don’t change the way we think and go back to the way Indigenous people have always thought. We call the earth our mother, the sky our father, the moon our grandmother, and the sun our grandfather. The Indigenous idea of relationality is basically that we are related to everything that’s living.

Could you speak to a specific example where those values were made tangible in one of your projects?

When I was selected with Antoine Predock to design the Indian Community School of Milwaukee, the school itself required there be an Indigenous designer on the design team. They’d created this design goal statement. One of the requirements was that the building had to have a connection to nature. So we asked ourselves: Is it just a visual connection? A physical connection? A spiritual connection? All of the above really was the answer. One of the other values they wanted was a 100-year building, meaning that this building has to be here in 100 years. So the materials had to be selected to last that long. We used limestone indigenous to that part of the country. We used a lot of copper. And we used white pines that were harvested from the Menominee Nation. Many of these trees were over 300 years old. A Menominee artisan helped us take the bark off and strip them. And the trees were taken down in a ceremony, like a funeral really, acknowledging that they gave their lives to the school, and we appreciated that.

I’m curious about your trickster series — trickster (itsnotatipi), 2018, an installation for the Bookworm Garden in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, and trickster II (itsnotawigwam), 2019, part of a group exhibition at the Haggerty Museum of Art in Milwaukee. You describe the trickster as reveling in paradox, and I feel like that’s related to a lot of what we’ve been talking about.

I was asked to apply for a residency at Bookworm Gardens, which represents aspects from children’s literature. I decided to use this as an opportunity to explain the role of the trickster in Indigenous storytelling, but I had to figure out how to represent the trickster because the way the trickster manifests is always different. It can be an animal that changes form. It can be an unexplainable phenomenon. It can be a hybrid.

I feel like Indigenous people are subject to stereotypes probably more than any culture. That’s why I don’t make things that look like a tepee or a wigwam or a longhouse. I just reject that because those typologies were from a specific time and a situation determined by what technology and materials were available. I want to make a contemporary artifact that defies those expectations but that still has certain cultural underpinnings. That’s in part why the trickster speaks to me.

I based the piece on a series of models I had made years before called Bending Out of Course that wasn’t for a commission or anything; they were just exploring what if I, as the architect, wasn’t trying to make a thing that was a metaphor for the culture. And I used trees that were harvested on-site, and I let the materials largely determine the form and configuration. I didn’t take the conventional role of the architect saying I’m going to envision this thing in my mind, then I’m going to draw it, and then I’m going to make it based on this drawing.

You relinquished that top-down control.

Exactly. I think as architects we rely too much on that mode. In Indigenous culture, we value dreams, feelings, visions, and hunches as equal to other forms of knowledge. Taking on the character of the trickster also allowed me to make certain statements — it’s the trickster who says you’re on stolen land, not me. It became a teaching device, and that’s what the trickster has always been in Indigenous storytelling. The trickster might try to eat too much or might try to gain too much recognition, and then you see the consequences. These stories teach us lessons related to how we should be treating each other and how we should be treating the planet, other animals, and our resources.

What was your experience at the Forge Project? It sounded like a really cross-disciplinary group of fellows, and getting away from strict specialization seems in line with what we’re talking about — moving away from more authoritative control.

It was a really amazing time. I was there for most of the month of August. When I got there, Edgar Heap of Birds, the Indigenous artist, was there as well. One of the great things about the fellowship is being able to meet people like that. I feel like in indigeneity, and I’ll use that as a sort of broad term, whether we’re creatives, researchers, artists, whatever, the disciplinary boundaries are much more permeable. There’s not a lot of things that separate us. If I’m talking to someone who’s a linguist or historian or whatever, those disciplinary boundaries are not as apparent as it might be in other facets of my life. The great thing about the Forge Project is it’s connecting us to people who are doing different things but thinking in a similar way and basically trying to achieve the same goal.

Indian Community School of Milwaukee sweatlodge changing room by studio:indigenous.

Perspective drawing of a fire circle to recognize Milwaukee’s Indigenous people at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee campus, completed 2021, designed by Chris Cornelius.

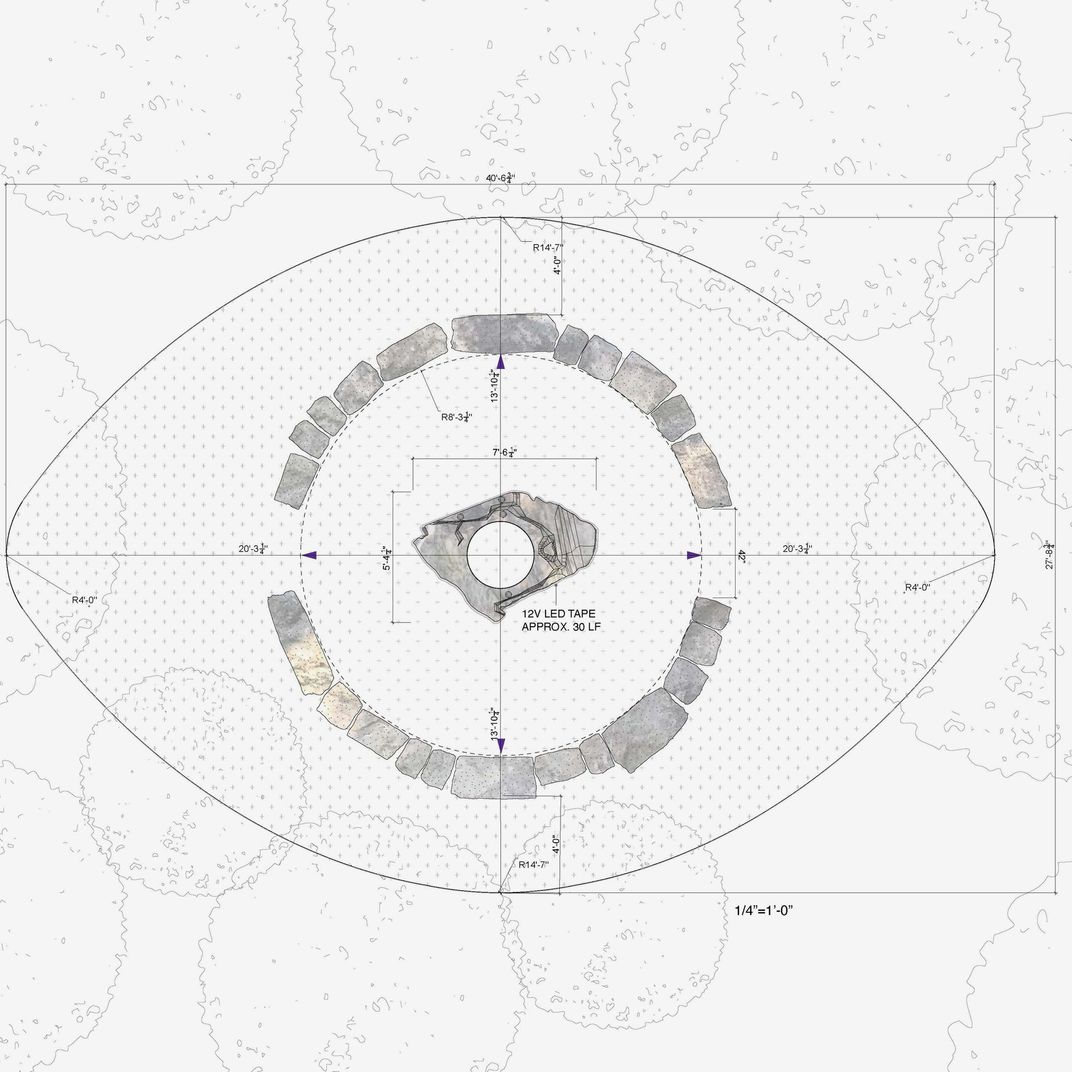

Plan for a fire circle to recognize Milwaukee’s Indigenous people at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee campus, completed 2021, designed by Chris Cornelius.

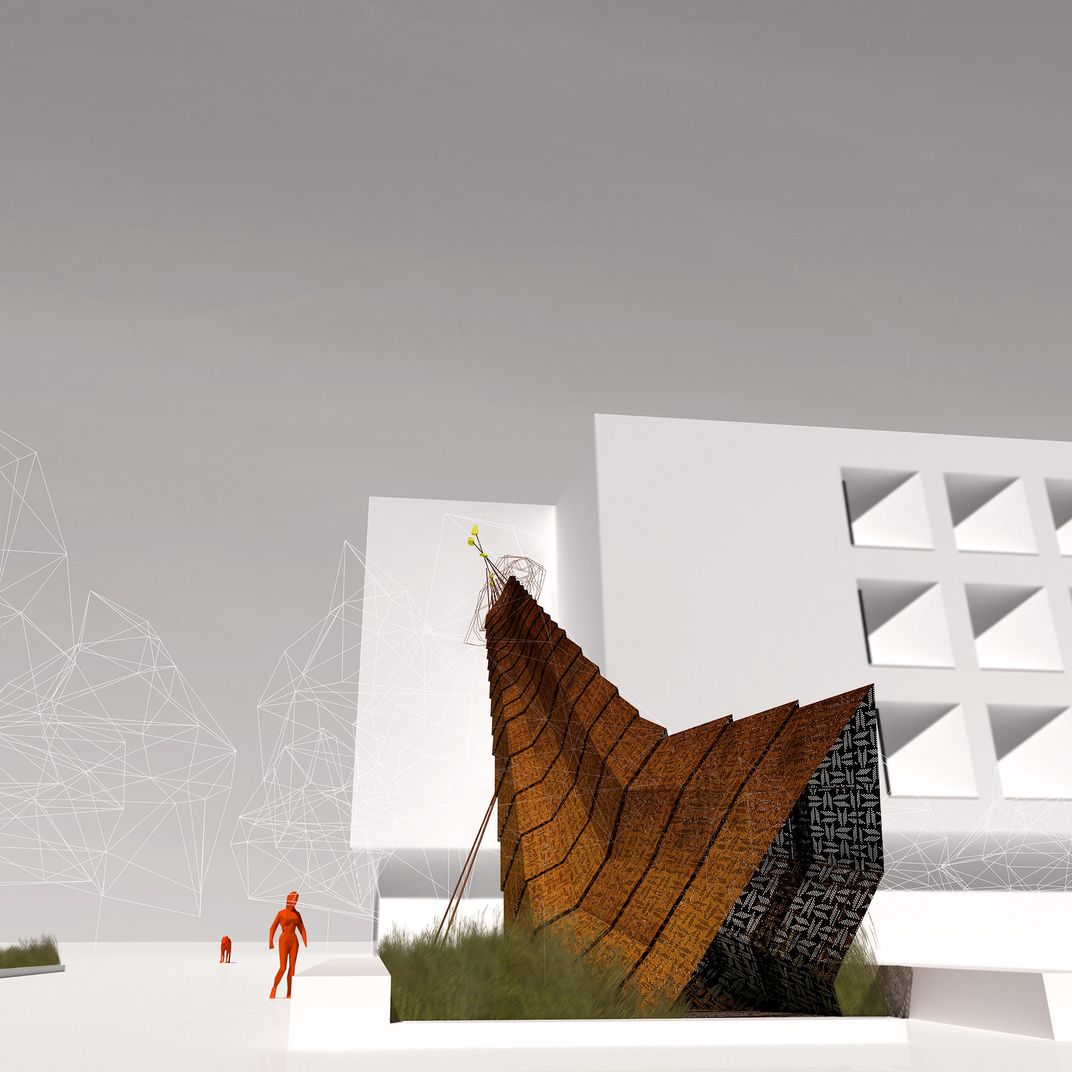

Otaeciah, a sculpture installed at Lawrence University. The word means “crane” in the Menominee language.

Indian Community School of Milwaukee sweatlodge changing room by studio:indigenous.

Perspective drawing of a fire circle to recognize Milwaukee’s Indigenous people at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee campus, completed 2021, designed by Chris Cornelius.

Plan for a fire circle to recognize Milwaukee’s Indigenous people at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee campus, completed 2021, designed by Chris Cornelius.

Otaeciah, a sculpture installed at Lawrence University. The word means “crane” in the Menominee language.